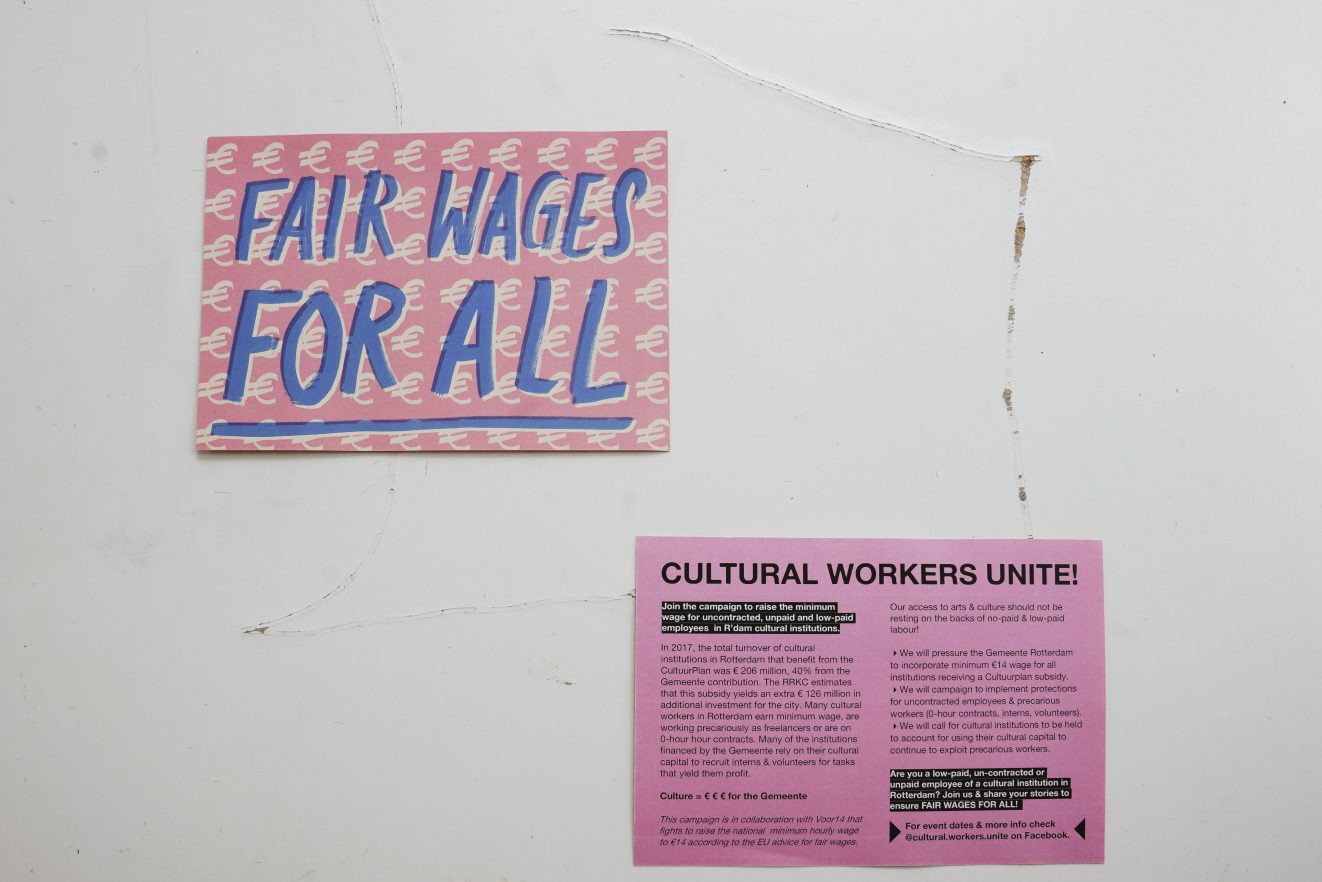

Interview met Cultural Workers Unite, activistische solidariteitsgroep en grassroots vakbond

Cultural Workers Unite wakkert solidariteit en bewustzijn aan als instrument om oneerlijke arbeidsomstandigheden aan te kaarten. Ze hanteren een ruime definitie van cultureel werk om zich ook sterk te kunnen maken voor de kwetsbare posities van bewaking, technici, schoonmakers of cafémedewerkers in culturele instellingen. Het collectief streeft ernaar om verschillende groeperingen met overlappende doelen bij elkaar te brengen en thema’s als racisme, gentrificatie en seksisme aan te pakken, kennis te delen en hun boodschap te versterken. De leden van Cultural Workers Unite die we voor dit artikel gesproken hebben, kiezen ervoor anoniem te blijven en spreken namens het collectief. This interview was originally conducted in English, you can read it under the Dutch version.

Waarom is de Fair Practice Code volgens jullie belangrijk?

Het is een goede gespreksstarter, maar de grote uitdaging schuilt in het toepassen van de code op specifieke situaties. Als een grote en een kleine instelling allebei zeggen: ‘Ik volg de Fair Practice Code’, dan betekent dat in beide gevallen iets anders. Over het algemeen zijn er bepaalde zaken die als taboe beschouwd worden, zoals het verlagen van het loon van de directeur om tot een evenwichtiger Fair Share te komen. Ook dit soort zaken zouden openlijk besproken moeten worden, zeker in het kader van bezuinigingen in de culturele sector. Wij denken dat er veel institutioneel vet is dat eerlijker verdeeld kan worden onder de mensen die het werk in een instituut uitvoeren. Wil de Fair Practice Code dit soort radicale kritiek geven of gaat het om een kleine aanpassing van de status quo? Wie mag bijvoorbeeld binnen de instelling bepalen of de Fair Practice Code wordt nageleefd? Hoe verlopen deze gesprekken? Wie is daarbij betrokken? Wij vinden dat deze soort machtsdynamiek op een transparante wijze besproken moet worden. Iedereen moet de mogelijkheid hebben om over deze kwesties te praten met diens werkgever, ook als je freelancer bent en in een precaire positie zit. Er moeten kaders zijn die dit gesprek binnen instellingen mogelijk maken, op zowel individueel als collectief niveau. Één van de belangrijkste doelen van de code is ongetwijfeld om mensen die niet de macht van een directeur hebben te ‘empoweren’, dus het is interessant om dat aspect verder uit te werken. Een medezeggenschapsraad is een goede plek om gesprekken over Fair Practice te voeren, maar het moet dan voor zzp’ers of anderen met een tijdelijk contract net zo toegankelijk zijn om mee te doen als voor een vaste medewerker, zodat alle belangen vertegenwoordigd zijn.

Cultural Workers Unite is in 2020 begonnen als een grassroots vakbond. Waarom voelden jullie de behoefte om een nieuwe vakbond te beginnen en niet bij een bestaande vakbond aan te sluiten?

We zijn niet echt een traditionele vakbond, maar meer een solidariteitsgroep. We voelden de behoefte tot zelforganisatie, om samen te komen en meer zelfgeorganiseerd oplossingen te bedenken voor bepaalde problemen. Een andere reden is dat er geen vakbond is die alle banen dekt die je als cultureel werker hebt. Als je bijvoorbeeld als kunstenaar werkt, zou het goed kunnen dat je ook in het café van een culturele instelling werkt. Je zou lid kunnen worden van FNV Horeca en de Kunstenbond, maar dan heb je geen ondersteuning die begrijpt wat het betekent om te jongleren met deze zeer verschillende arbeidsvoorwaarden, arbeidscontracten, enzovoorts. Er wordt door kunstacademies niet voldoende aandacht besteed aan het soort banen dat je nodig hebt om je artistieke werk duurzaam te kunnen doen. De verwevenheid van dit soort verschillende banen kun je als iemand die werkzaam is in de culturele sector niet los van elkaar zien. Je doet al deze verschillende dingen tegelijkertijd. Ook speelde er op dat moment iets binnen een specifieke instelling. In het café werkte een uitzendkracht die niet gezien werd als onderdeel van de culturele instelling en daarom dus niet onder de Kunstenbond viel. Deze medewerkers vormen duidelijk een groot onderdeel van deze culturele instelling, maar worden behandeld alsof ze inwisselbaar en misbaar zijn. Hetzelfde geldt voor schoonmakers en bewakers: toen covid begon, waren zij de eersten die eruit gegooid werden. Ze worden niet erkend als cultureel werker omdat het uitzendkrachten zijn. Geldt de Fair Practice Code ook voor hen? Het waren deze zeer reële dingen die ervoor gezorgd hebben dat wij ons af begonnen te vragen: “wie waarderen we echt?”

Details locatie gesprek, bij de ruimte van VARIA

CWU heeft verschillende problemen aangekaart die verband houden met de precaire arbeidsomstandigheden in de culturele sector. Naast Fair Pay onder andere ook top-down besluitvorming en ongezonde concurrentie. Met beperkte middelen moeten jullie ongetwijfeld kiezen welk onderwerp het meest urgent is: hoe maken jullie die keuze? En hoe bepaal je de meest geschikte methode om deze kwesties aan te pakken?

De prioriteit is meestal gebaseerd op een urgente noodzaak. Als er een specifiek geval is van iemand die een probleem heeft dat te maken heeft met eerlijk loon, dan richten we ons op Fair Pay. We zijn niet gespecialiseerd in specifieke vraagstukken, maar hebben ervaring met situaties waarin mensen tijdelijke contracten hebben, worden uitbesteed, geen eerlijk loon krijgen of zich in een ongezonde werkomgeving bevinden. Dat is een breed spectrum aan ervaring dat zich verdiept door waar we urgentie voelen. Dit is ook de methode van solidariteitsgroepen zoals Vloerwerk in Amsterdam, of de Radical Riders die mensen in de bezorgdiensten proberen samen te brengen. Het is een collectieve hulp structuur die in actie komt op het moment dat iemand met een probleem aanklopt. Vervolgens maak je een strategie om met dit probleem om te gaan. De aanpak verandert wanneer je te maken hebt met een individuele werkgever of een instelling. Specifiek voor de institutionele culturele sector is de meest effectieve methode helaas vaak om ze publiekelijk ter verantwoording te roepen, omdat ze graag het imago van “divers”, “rechtvaardig” en “niet op winst gericht” willen behouden. Dus aan de ene kant werken we aan specifieke zaken, waarin we een werker volgen die het voortouw neemt en bepaalt waar hij/zij mee instemt. Het andere deel van onze activiteiten is meer educatief van aard; hoe kunnen we samen leren over zaken als bijvoorbeeld uitbuiting en zo onze positie versterken? Jongeren die net van de kunstacademie komen, hebben de slechtste aspecten van de culturele sector vaak al geïnternaliseerd. Ze verwachten het absolute minimum, weten niet wat hun rechten zijn en wat ze kunnen vragen. Wij vinden dat dit niet normaal is en dit zou meer besproken moeten worden. Zoiets als de anti-gentrificatieschool die we de laatste tijd hebben georganiseerd, gaat over de complexiteit van het zijn van een culturele werker. Het gaat om de ervaring dat je geïnstrumentaliseerd wordt voor de gentrificatie van bepaalde gebieden en een wijk mag verbeteren, maar dat je vervolgens ook weer ontheemd wordt omdat die wijk daardoor niet meer te betalen is voor jou als kunstenaar. Het gaat dus meer om het navigeren door dit soort complexiteit en realiseren dat je worsteling als cultureel werker niet gescheiden kan worden van andere maatschappelijke strijd rond huisvesting. We willen gesprekken aangaan over eerlijk loon als een issue in de culturele sector, maar het is ook een probleem voor veel mensen in andere sectoren. Ik denk dat dit ook één van onze benaderingen is: hoe kunnen we ons verbinden en solidariteit tonen die verder gaat dan alleen de culturele sector?

“We proberen ons meer te concentreren op het opbouwen van solidariteit en het bereiken van mensen die ondersteuning nodig hebben, in plaats van gratis advies geven aan instellingen over hoe ze het beter kunnen doen.” Waarom wil je deze instellingen geen advies geven?

De vraag die daarbij hoort is: ‘waar vindt cultuur plaats?’ Veel cultuur vindt plaats buiten instellingen om. Gatekeeping gebeurt niet alleen aan de deur van de instelling; het gebeurt bijvoorbeeld al wanneer mensen beslissen of ze naar een kunstacademie gaan. Wij denken dat cultuur volledig buiten de institutionele opzet kan plaatsvinden, die standaard bepaalde mensen uitsluit. Het veranderen van instellingen vereist zoveel meer werk dan proberen iets anders op te bouwen. Wij richten ons op waar cultuur daadwerkelijk plaatsvindt, op alle alternatieven die zelfgeorganiseerd zijn of door een gemeenschap worden geleid. We zeggen niet dat er geen instellingen zouden moeten zijn, maar ze monopoliseren discussies als het gaat om cultuur, de beschikbare financiering enzovoort. Neem bijvoorbeeld diversiteit en inclusie. Grote instellingen krijgen veel geld om diverser te worden. Inclusiviteit gaat voor hen over het opnemen van mensen in hun huidige manier van doen: ik betrek jou in mijn ding en jij maakt dit divers. Terwijl het zou moeten zijn: we worden geleid door jou en we moeten onze werkwijze helemaal heroverwegen omdat je hier nooit eerder welkom was. Je hebt een radicale herstructurering nodig op basis van de mensen die er voorheen niet bij hoorden en die vind je in kleinere, nieuwe initiatieven die direct gefinancierd zouden moeten worden. Dat is wat we eerder ook bedoelden met het aanpassen van een bestaande structuur die nooit een radicale verandering zal ondergaan. Er zijn veel groepen die zich wel op deze institutionele veranderingen richten, zoals Platform BK en Kunsten92. Deze lobbygroepen hebben de macht om rechtstreeks met mensen te praten die macht hebben. We willen ons richten op zaken die niet onder deze andere belangengroepen vallen. De keuze om ons niet te richten op grote instellingen heeft ook te maken met arbeid. Als we iemand helpen door te bemiddelen tussen hen en een instelling, dan kan het soms zo ver gaan dat je denkt: ‘wow, we verzetten nu wel heel veel werk om de instelling beter te laten werken.’ We willen werknemers ondersteunen, maar er is een punt dat je moet stoppen met onbetaalde arbeid om instellingen te laten doen wat ze zelf zouden moeten en kunnen doen.

Selectie aan magazines en publicaties van VARIA leden en vrienden

Er zijn veel gemeenschappen en groepen waar CWU zich mee engageert die zich richten op kwesties als gentrificatie, racisme, solidariteit met Palestina en vrouwenemancipatie. Solidariteit tussen al deze groepen is voor jullie belangrijk. Waarom betrekken jullie deze bredere thema’s bij jullie activiteiten?

Dit zijn vraagstukken die de culturele sector direct raken. Zo was solidariteit met Palestina een discussie binnen kunstinstellingen. Het was een groepering die werkzaam was binnen de Willem de Kooning Academie die geleid werd door studenten. Wat wij doen is deze groepen ondersteunen. Het draait om het uitvergroten van het bereik van strijd die met de culturele sector kruist, hetzij volledig, direct of indirect. Sommige affiches van de Woonopstand hingen ook in Roodkapje of Showroom MAMA, dus instellingen pakken zelf ook een aantal van deze kwesties op. Solidariteit gaat verder dan vraagstukken binnen de culturele sector. Er zijn veel raakvlakken met andere kwesties. Wij voelen dat er een kracht ligt in het erkennen van deze complexiteit. De strijd voor duurzamere en betaalbare studio’s voor kunstenaars werd versterkt door het maken van een connectie met mensen die ook huisvesting problemen ervaren. Huisvesting gaat over een plek om te wonen, maar ook om een plek om te werken. De strijd om betaalbare studio’s kruist met de strijd om woonruimte, aangezien cultuurwerkers vaak worden opgezet tegen mensen in precaire woonsituaties als ‘antikraak’. Als de gemeente haar panden niet had verkocht aan ontwikkelaars en als leegstand goed werd aangepakt -niet door antikraak maar door andere vormen van collectief bezit of beheer toe te staan - dan zouden we niet hoeven te concurreren om ruimte. Er moet voldoende ruimte zijn voor huisvesting en er moet voldoende ruimte zijn voor gemeenschapsorganisatie en culturele productie.

Wat kunnen culturele werkers, als individuen, zelf doen om te werken aan een eerlijke praktijk? Stel meer vragen als: ‘is dit contract eerlijk? Hoeveel krijg je daarvoor betaald? Wordt iedereen op mijn werkplek eerlijk betaald?’

Accepteer niet wat als de “standaard” wordt beschouwd zonder die aan te vechten. Zoek bondgenoten op je werkplek en als dat niet mogelijk is, zoek dan mensen in een vergelijkbare positie. Probeer niet in een competitieve mindset te vervallen en blijf open delen hoeveel je betaald krijgt. Wees transparant: ‘dit is hoeveel ik mijn klanten in rekening breng als starter en freelancer. Hoeveel vraag jij daarvoor? Is dit genoeg voor mij om de verzekering te betalen? Krijg ik hetzelfde als iemand die bij een instelling werkt?’ Praat ook over praktische zaken als boekhouden en al die saaie dingen. Zeker als je niet Nederlands bent is bijvoorbeeld het doen van je belastingen erg ingewikkeld. Zorg ervoor dat je zonder schaamte over dit soort dingen kunt praten. Er is veel schaamte verbonden aan het vragen van geld voor ‘waar je van houdt’, maar culturele arbeid is ook arbeid, dus daar moeten we aan voorbij.

—

Interview with Cultural Workers Unite, activistic solidarity group and grassroots union

Cultural Workers Unite’s activities revolve around building solidarity and awareness as a tool to address unfair working conditions. They consciously use an expansive definition of cultural work to include precarious jobs as those of guards, technicians, cleaners, or café staff within cultural institutions. The collective tries to bring various groups with overlapping goals together to address issues like racism, gentrification and sexism, to share knowledge and to amplify their message. The members of Cultural Workers Unite we spoke to for this article choose to stay anonymous and speak on behalf of the collective.

According to you, why is the Fair Practice Code important?

It’s a good conversation starter, but the big challenge is applying the code to specific cases. If a big institution and a small one both say, ‘I follow the Fair Practice Code’, that means something completely different in both cases. In general, there are certain things that are considered taboo, like lowering the wage of the director in order to achieve a more balanced Fair Share. These things should also be openly discussed, especially in the context of budget cuts in the cultural sector. We think there’s a lot of institutional fat that just stays there and could be distributed more equitably to the people that do the work. Does the Fair Practice Code want to embed this kind of radical criticality or is it about slightly tweaking the status quo? For instance, who inside the institution gets to say whether the Fair Practice Code is being adhered to? How do these conversations happen? Who is involved in them? We think these power dynamics should be addressed in transparent ways. You should have the possibility to talk about these issues with your employer, even if you are a freelancer and you’re in a precarious position. There should be frameworks that allow for this conversation to happen, not just on an individual level, but also at a collective level within the institutions. One of the key goals of the code is surely to empower people who don’t have power in the way a director does, so fleshing that part of it out is interesting. A participation council is a good way to start discussions about what constitutes a fair practice, however this should be easy for freelancers or others with temporary contracts to join, so that all interests are represented.

Cultural Workers Unite started as a grassroots union in 2020. Why did you feel the need to start a new union and not join an existing one?

We’re not really a traditional union, we’re more like a solidarity group. We felt a need for self-organization, to come together and think of more self-organized solutions to certain problems. Another reason was that there is not one union that can cover all the types of jobs you do as a cultural worker. For instance, if you work as an artist, you might also at a cafe in a cultural institution. I could join FNV Horeca and the Kunstenbond, but then you also need another framework that understands all the specificities of having to juggle these very different labor conditions, labor contracts, etc. There’s not enough information disseminated by art schools about the types of jobs you will need to have to make your artistic job sustainable and durable. The interrelatedness of these different kinds of jobs is not something you can separate as someone working in the cultural sector. You do all these different things at the same time. We also saw at that moment in time that there was something playing out within one specific institution. There was an outsourced worker in the cafe who wasn’t seen as part of the cultural institution and who was therefore not covered by the Kunstenbond. These employees are obviously a massive part of this cultural institution’s life but were treated as though they were expendable. The same goes for cleaners and guards: when covid came, they were the first to be kicked out. They’re not recognized as a cultural worker because they’re outsourced. Does the Fair Practice Code also apply to them? We think it was these very real things happening that made us question ‘who do we really value?’

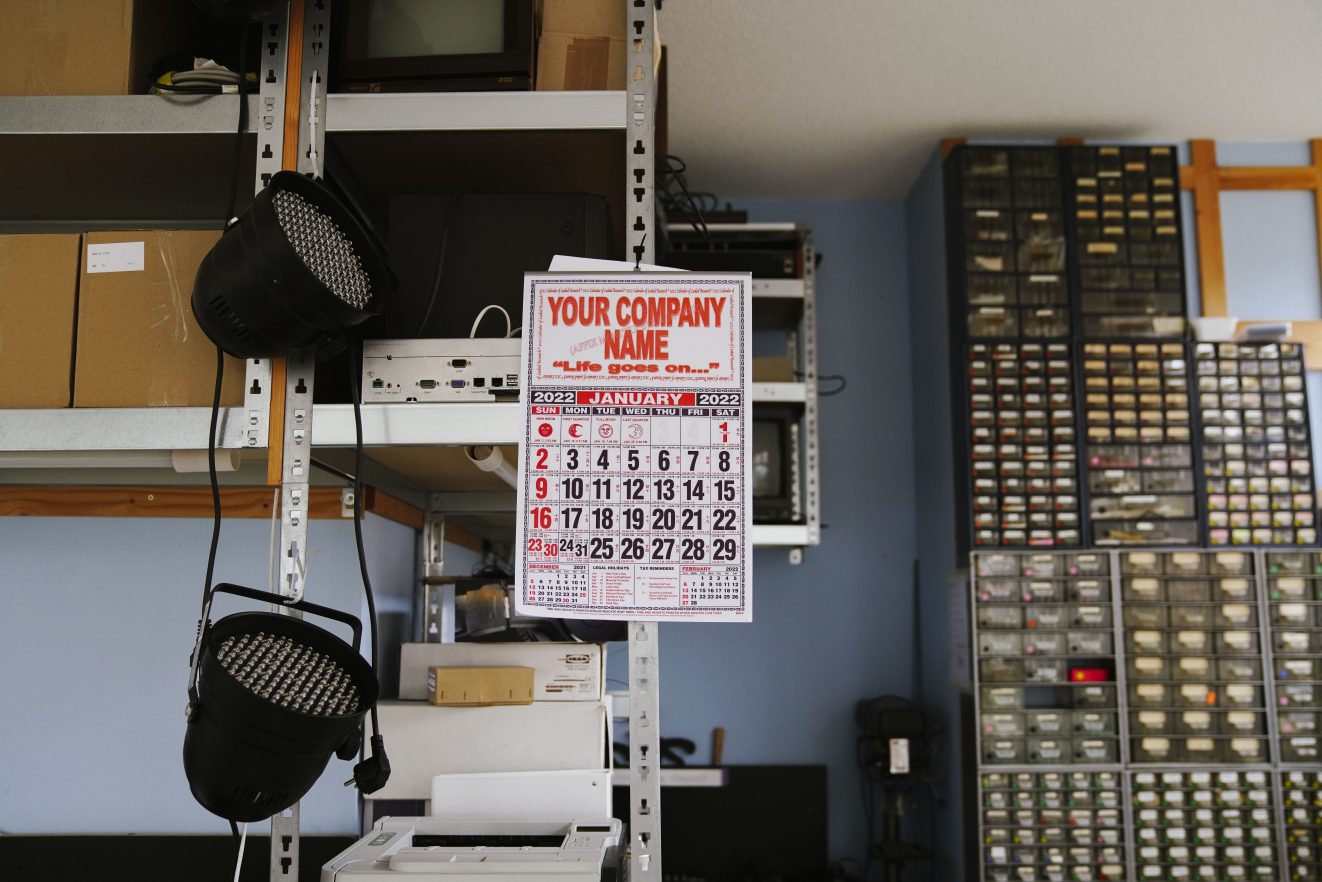

2022 kalender van Leaked Research “Life goes on” a project by Your Company Name (Clara Balaguer and Cengiz Mengüç)

CWU has addressed several issues related to the precarious working conditions in the cultural sector. Besides Fair Pay, some examples are top-down decision making, unhealthy competition and gatekeeping. With limited means, how do you choose which of these are the most urgent? And how do you decide the best method to address them?

It’s usually based on immediate need. If there is a specific case of someone who has a problem that has to do with fair pay, then we will focus on fair pay. We wouldn’t say we specialize in specific issues, but we have experience with situations where people have temporary contracts, are being outsourced, do not receive fair pay or find themselves in an unhealthy work environment. There is a broad spectrum that deepens by what we feel is urgent. This is also the method of solidarity groups like Vloerwerk in Amsterdam or the Radical Riders group that tries to organize people working in the delivery services. They focus on a mutual aid framework, but they start from the moment that someone comes to them with a problem. Then you create a strategy of how to deal with this problem. The approach changes depending on if you’re dealing with an individual employer or an institution. For the institutional cultural sector specifically, unfortunately, often the most effective method is trying to call them out as they need to maintain the image of being “diverse”, “equitable” and “not profit driven”. So on the one hand there’s working on the specific cases, which is about going along with the worker, what they consent to and taking their lead. The other part of our activities is more educational; how can we come together to learn about issues like exploitation and thereby strengthen our positions. Young people who have just come out of art schools have already internalized the worst parts of the cultural sector. They expect the bare minimum and do not know what their rights are and what they can ask for. We think that’s not normal and should be discussed more. Something like the anti-gentrification school we have been organizing lately deals with the complexity of being a cultural worker, both being instrumentalized for the gentrification of certain areas but also suffering from it as you are eventually displaced. So it is more about navigating complexity and realizing your struggles as a cultural worker cannot be separated from other societal struggles. We want to initiate and encourage serious conversations about fair pay as an issue in the cultural sector, but this is also an issue for a lot of people working in other sectors. I think that’s another one of our approaches: how can we connect and show solidarity beyond the cultural sector?

“We try to focus more on solidarity building and reaching out to people that need support rather than giving free advice to institutions about how they could do better.” Why don’t you want to give advice to these institutions? That’s a question of ‘where does culture happen’?

A lot of culture happens outside of institutions. Gatekeeping does not just happen at the doors of the institution; for example, it already happens when people decide whether to go to an art school. We think culture can happen completely outside of this institutional setup, which by default excludes certain people. Changing institutions requires so much more work than trying to build something different. We focus on where culture actually happens and on all the alternatives that are self-organized or community led. We are not saying there shouldn’t be institutions, but they do monopolize discussions when it comes to culture, the available funding etcetera. Take diversity and inclusion for example. Big institutions get a lot of money to become more diverse. Inclusivity to them is about including people in their existing way of doing things: I include you in my thing and you make this diverse. Whereas it should be: we’re led by you, and we need to rethink the way we work because you weren’t ever welcome here before. You need radical restructuring based on the people who weren’t included before and that can be found in smaller, new initiatives that should be funded directly. That’s what we meant before about making these tweaks to an existing structure that’s never going to have a radical change. There are many groups that do focus on these institutional changes like Platform BK and Kunsten92. These lobbying groups have the power to talk directly to people who have power. We want to also focus on things that are not covered by these other groups. The choice not to focus on institutional change concerns labor as well. If we help someone by being an intermediary between them and an institution, then sometimes it can get to a point where you’re thinking: ‘wow, we’re doing a lot of the labor to make the institution do a better job.’ We want to support workers, but there’s a point you must stop doing unpaid labor to make these institutions do what they should and could obviously do themselves.

Details locatie gesprek, bij de ruimte van VARIA

There are many communities and groups CWU has been engaging with, addressing issues like gentrification, racism, solidarity with Palestine and female emancipation. Solidarity between all these groups seems important to you. Why do you include these broader issues as a cultural workers collective?

These are issues that directly affect the cultural sector. For example, the solidarity with Palestine was a discussion within art institutions. Solidarity with Palestine was a group that was working within the Willem de Kooning and was led by students. What we do is support these groups. It’s a lot of amplification of other struggles that intersect with the cultural sector, either completely, directly, or indirectly. Some posters of the Woonopstand were also in Roodkapje or Showroom MAMA, so institutions themselves take up some of these causes. Solidarity goes beyond issues within the cultural sector. There are many overlaps with other issues. We feel there is a strength in acknowledging these complexities. The fight for more sustainable, and affordable studios for artists, was really strengthened by connecting with people who have similar struggles in slightly different ways, like housing. Housing is about a place to live, but also a place to work. The fight for affordable studios intersects with the fight for housing as often cultural workers are pit against people in precarious housing situations such as ‘antikraak’ (anti-squatting guardian schemes). If the municipality had not sold its properties to developers and if vacancy was tackled properly -not through antikraak but through allowing other forms of collective ownership or management – then we would not have to compete for space. There needs to be enough space for housing, and there needs to be enough space for community organizing, as well as cultural production.

What can cultural workers, as individuals, do themselves to work towards a fair practice?

Ask more questions such as: ‘is this contract fair? How much are you getting paid for that? Is everyone in my workplace paid fairly?’ Also, do not accept what is considered the “standard” without challenging it. Find allies within your workplace, but if that is impossible, find people in a similar position. Try not falling into this competitive mindset and keep sharing how much you get paid. Be transparent: ‘this is how much I charge my clients as a starter and a freelancer. How much do you charge? Is this enough for me to pay insurance? Do I get the equivalent thing that someone who works an institution does?’ Also talk about practical things like accounting and all these boring things. Especially for someone who isn’t Dutch, doing you taxes can be quite difficult for example. Make sure you can talk about this stuff without shame. There’s a lot of shame attached to asking money for ‘what you love’, but cultural labor is also labor so we must move past that.

Tekst: Manus Groenen

Fotografie: Liza Wolters